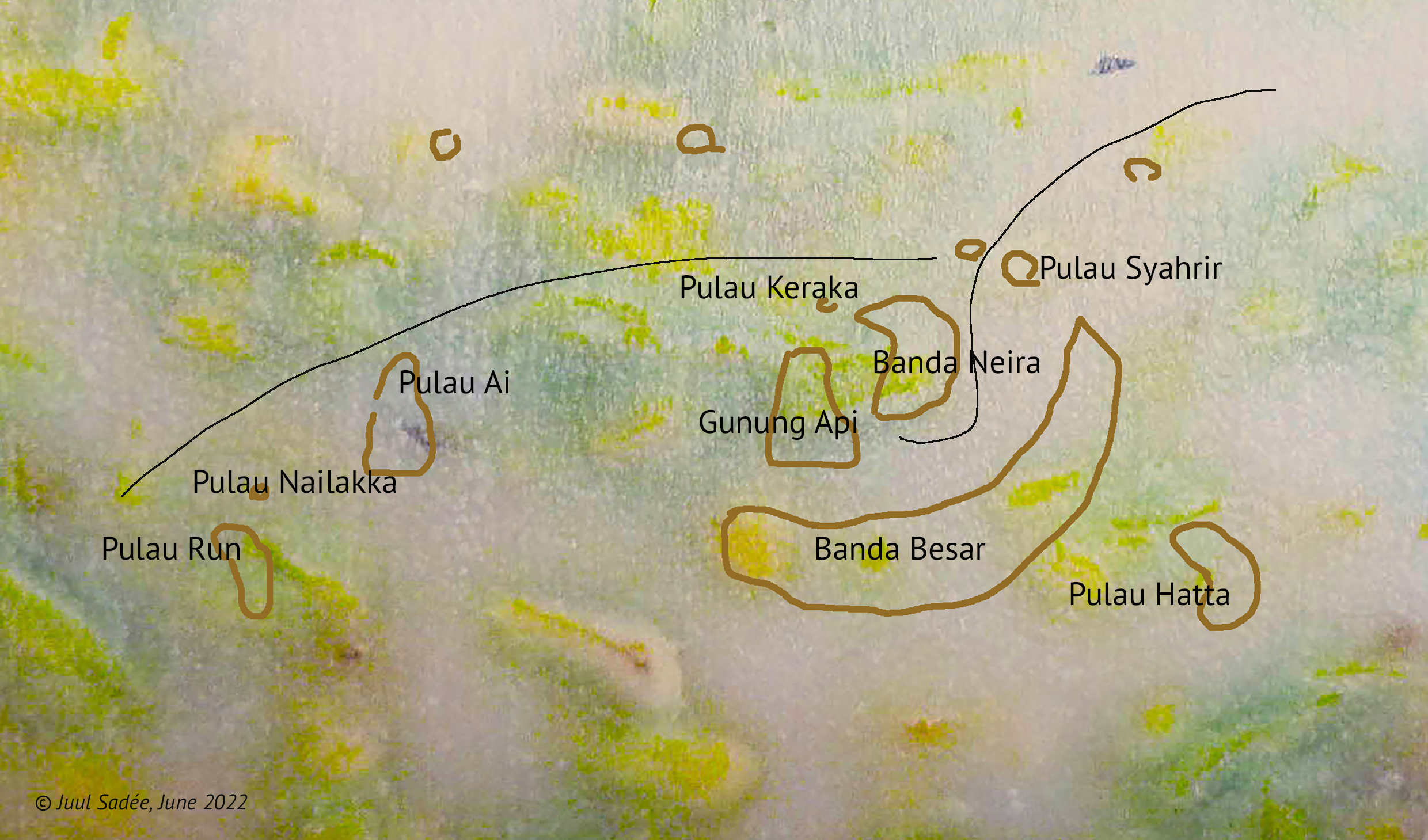

map by Juul Sadée 01-07-2022

times to come we will learn by reading, talking, doing and tickling the imaginations of our own and those of others

waktu yang akan datang kita akan belajar dengan membaca, berbicara, melakukan dan menggelitik imajinasi kita sendiri dan orang lain

BOOKTITLES / JUDUL BUKU

Hans Straver; ‘Vaders en dochters’ Molukse historie in de Nederlandse literatuur van de negentiende eeuw en haar weerklank in Indonesië

Roy Ellen; ‘On the Edge of the Banda Zone’, Past and Present in the Social Organization of a Moluccan Trading Network

Hans Straver; ‘De zee van verhalen’, de wereld van Molukse vertellers

Suleman Latukau; ‘Lani Nusa, Lani Lisa’, Kapata dari Morela

Muhammad Farid, ‘Tana Banda’, Essay-Essay tentang Mitos, Sejarah, Sosial, Budaya Pulau Banda Neira

Otto Egberts; ‘Coen en zijn tijd’

Layne Redmond, ‘When the Drummers Were Women’

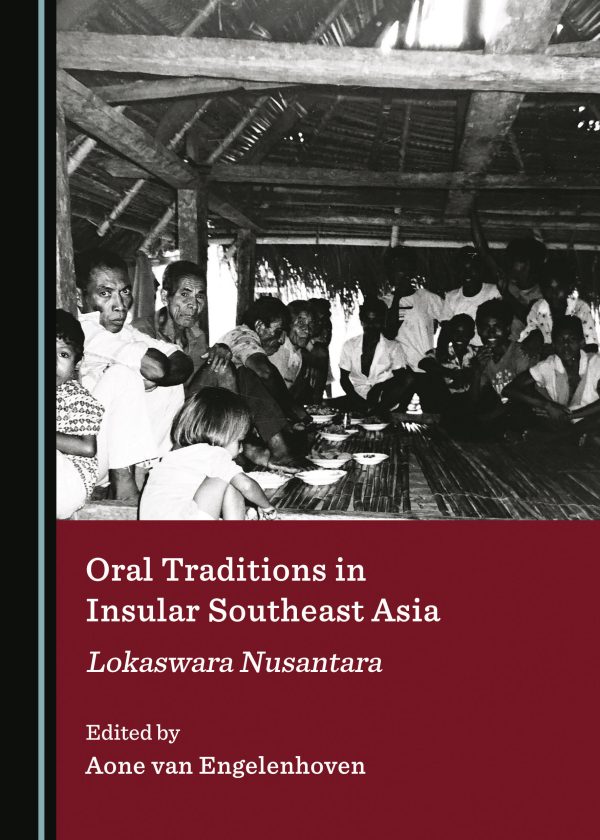

Oral Traditions in Insular Southeast Asia

Lokaswara Nusantara

Edited By: Aone van Engelenhoven

Insular Southeast Asia’s extraordinary cultural diversity is matched by its heterogeneous oral traditions. This volume explores oral poetry and storytelling from different corners of the region through perspectives including ecocriticism, poetics, linguistics, and politics.

Chapter Nine page 207 “Who is Bhoi Kherang?”: Perspectives on a Special (Hi)story of Bhoi Kherang Muhammad Farid and Juul Sadée

Wacana Press, Vol. 24 > No. 2 (2023

Muhammad Farid, Universitas Islam Internasional (UII-Dalwa), East Java and Universitas Banda Naira, MalukuFollow

Juul Sadée, University of Maastricht, The NetherlandsFollow

Abstract

The historiography of Banda has paid little attention to the existence of women. Stories involving women are mainly about romance, family, and suffering. In reality, the existence of “Mama Lima” (groups of five women) is very strong in the Banda tradition (adat). They are the carriers of knowledge and tradition, a consequence of matriarchy. They determine the content and implementation of adat ceremonies like Buka kampong, forming the set of social norms and customary law of the community. Mama Lima groups are a living example of women throughout the ages who have played a significant role in welfare, the environment, religion, spiritualism, education, and nature. This article discusses the position of women in Banda from its colonization in 1609: defending their land, customs, and descendants, to this day. The results show that Banda women have been practising gender equality for centuries, passing their functions on to the younger generation, and have become an example for all Bandanese today.

ARTICLES / ARTIKEL

Muhammad Farid and Juul Sadée; “Mama Lima; The significance of women’s role in protecting nature, nurture, and culture in Banda Islands”

Andrea Acri, Roger Blench, Alexandra Landmann; ‘Introduction, Re-connecting Histories across the Indo-Pacific’

Peter Lape; ‘Historic Maps and Archaeology’ as a Means of Understanding Late Precolonial Settlement in the Banda Islands, Indonesia

Muhammad Farid; ‘Commemorating the Banda Genocide in 1621’; for what and who?

PALA, NUTMEG TALES OF BANDA, Online exibition By Westfries Museum, Hoorn, Holland www.pala.wfm.nl

Lokaswara Nusantara

Diedit Oleh: Aone van Engelenhoven

Keragaman budaya Asia Tenggara yang luar biasa diimbangi oleh tradisi lisannya yang heterogen. Volume ini mengeksplorasi puisi dan penceritaan lisan dari berbagai penjuru kawasan melalui berbagai perspektif, termasuk ekokritik, puitika, linguistik, dan politik.

Bab Sembilan halaman 207 “Siapakah Bhoi Kherang?”: Perspektif tentang (Hi)story Khusus Bhoi Kherang Muhammad Farid dan Juul Sadée

Wacana Press, Vol. 24 > No. 2 (2023

Muhammad Farid, Universitas Islam Internasional (UII-Dalwa), East Java and Universitas Banda Naira, MalukuFollow

Juul Sadée, University of Maastricht, The NetherlandsFollow

Abstrak

Historiografi Banda kurang memperhatikan keberadaan perempuan. Kisah-kisah yang melibatkan wanita terutama tentang romansa, keluarga, dan penderitaan. Kenyataannya, keberadaan “Mama Lima” (kelompok lima perempuan) sangat kuat dalam tradisi (adat) Banda. Mereka adalah pembawa pengetahuan dan tradisi, konsekuensi dari matriarki. Mereka menentukan isi dan pelaksanaan upacara-upacara adat seperti kampung Buka, membentuk seperangkat norma sosial dan hukum adat masyarakat. Kelompok Mama Lima merupakan contoh hidup perempuan sepanjang zaman yang telah berperan penting dalam kesejahteraan, lingkungan, agama, spiritualisme, pendidikan, dan alam. Artikel ini membahas tentang posisi perempuan di Banda sejak penjajahannya pada tahun 1609: mempertahankan tanah, adat, dan keturunannya hingga saat ini. Hasilnya menunjukkan bahwa perempuan Banda telah mempraktekkan kesetaraan gender selama berabad-abad, mewariskan fungsinya kepada generasi muda, dan menjadi teladan bagi seluruh masyarakat Banda saat ini.

The sea, marble, textiles.

by Juul Sadée

The photo above shows a marble sculpture depicting a bishop. He is dressed in a luxurious robe with lace and embroidery decorations. His cape is closed with a special button.

This sculpture is located in the cathedral of Saint John the Baptist in Ghent in today’s Belgium.

The construction of this Romanesque, Catholic church started in 942. From the 12th century, the church grew larger and richer with its peak in the 16th and 17th centuries as the Cathedral of the Diocese of Ghent, founded in the 16th century.

The sculpture and the cathedral symbolize the prosperity in Europe, brought by, among other things, the textile trade with Asia.

This trade route by sea via South Africa, Italy and Spain to 12th century Paris (France) made Paris a very prosperous city. Here the silk industry flourished. This allowed the kings to dress in the most luxurious robes and have their houses decorated with the most beautiful embroidered silks. It was very special for that time that it was mainly women, mostly from Italy, who held sway in the silk industry. Around the 16th century the accent shifted to Ghent. The textile industry flourished there until the end of the 20th century.

The marble bishop in this cathedral is carved from a block of very beautiful white Italian marble from Carara (Tuscany). The world famous Michelangelo had his quarries here. This marble was also used as ballast to balance the great ships on the long overseas voyages, and so it happened that the colonial buildings and houses in Indonesia were provided with Italian marble.

Wind and sea currents directed the ships through the Banda Archipelago. Cotton and silk from India and China and spices from Banda found their way to Europe. It was a hard-won trade. Sometimes Jan Pieterszoon Coen used the enormous bales of textile as a defensive wall during the naval battles. His fleet fought the English for the exclusive right to trade with Banda. The destroyed cotton and silk were thrown overboard.

Jan Pieterszoon Coen, governor-general in the service of the VOC (Dutch East India Company) resided for a few years at Banda’s Fort Belgica. The beautiful colonial buildings on Banda Neira, including the famous Istana Mini, are of a later date.

Back in the Low Countries (today’s Netherlands) Jan married Eva Ment in 1625. They lived in Batavia (todays Jakarta) where Jan died in 1629.

Juul Sadée, November 2020

Laut, marmer, tekstil.

by Juul Sadée

Foto di atas menunjukkan patung marmer yang menggambarkan seorang uskup. Ia mengenakan jubah mewah dengan hiasan renda dan bordir. Jubahnya ditutup dengan kancing khusus.

Patung ini terletak di katedral Santo Yohanes Pembaptis di Ghent di Belgia saat ini.

Pembangunan gereja Katolik bergaya Romawi ini dimulai pada 942. Sejak abad ke-12, gereja tumbuh lebih besar dan lebih kaya dengan puncaknya pada abad ke-16 dan ke-17 sebagai Katedral Keuskupan Ghent, yang didirikan pada abad ke-16.

Patung dan katedral melambangkan kemakmuran di Eropa, antara lain dibawa oleh perdagangan tekstil dengan Asia.

Rute perdagangan melalui laut melalui Afrika Selatan, Italia dan Spanyol ke abad ke-12 Paris (Prancis) menjadikan Paris kota yang sangat makmur. Di sini industri sutra berkembang pesat. Hal ini memungkinkan para raja untuk mengenakan jubah termewah dan rumah mereka didekorasi dengan sulaman sutra yang paling indah. Sangat istimewa untuk saat itu bahwa sebagian besar wanita, kebanyakan dari Italia, yang memegang kekuasaan di industri sutra. Sekitar abad ke-16 aksen bergeser ke Ghent. Industri tekstil berkembang pesat di sana hingga akhir abad ke-20.

Uskup marmer di katedral ini diukir dari balok marmer putih Italia yang sangat indah dari Carara (Tuscany). Michelangelo yang terkenal di dunia memiliki tambangnya di sini. Marmer ini juga digunakan sebagai pemberat untuk menyeimbangkan kapal-kapal besar dalam perjalanan panjang ke luar negeri, dan kebetulan bangunan dan rumah-rumah kolonial di Indonesia diberi marmer Italia.

Arus angin dan laut mengarahkan kapal melalui Kepulauan Banda. Kapas dan sutra dari India dan Cina serta rempah-rempah dari Banda sampai ke Eropa. Itu adalah perdagangan yang diperoleh dengan susah payah. Kadang-kadang Jan Pieterszoon Coen menggunakan bal-bal tekstil yang sangat besar sebagai tembok pertahanan selama pertempuran laut. Armadanya melawan Inggris untuk mendapatkan hak eksklusif berdagang dengan Banda. Kapas dan sutra yang hancur dibuang ke laut.

Jan Pieterszoon Coen, gubernur jenderal yang melayani VOC (Perusahaan Hindia Timur Belanda) tinggal selama beberapa tahun di Benteng Belgica Banda. Bangunan kolonial yang indah di Banda Neira, termasuk Istana Mini yang terkenal, sudah ketinggalan zaman.

Kembali ke Negeri-negeri Rendah (sekarang Belanda) Jan menikah dengan Eva Ment pada 1625. Mereka tinggal di Batavia (sekarang Jakarta) di mana Jan meninggal pada 1629.

Cross cultural contact and interaction.

by Juul Sadée

Who are the residents of Banda? What is typical Banda’s culture?

It is a given that from 500 AD there were already regional relations between the islands of the South East and South West Moluccan archipelago. But the Chinese also visited the archipelago in the centuries prior to the 10th century.

From the 10th century onwards, incidental contacts arose when traders from Java and the Lesser Sunda islands visited the Banda archipelago. This created trade networks with South East Asia.

Turks, Persians, Bengalis, Gudjeratis, Chinese, Japanese, Malays, Javanese, Makassars, Ternatans, Tidorese, Seramese and other migrants from islands located around the Banda Sea settled in new settlements on Banda Neira, Banda Besar and Ay from 14th century. Conflicts arose as the established residents focused on the regional spice trade while the newcomers engaged in national trade.

European influences came with the Portuguese visiting the Banda Islands from the early 16th century, followed by the English and the Dutch.

When I ask my Moluccan friends about their ancestors, place of birth and place of residence, it becomes clear that many interracial marriages have taken place with varying places of residence throughout the Indonesian archipelago. For example, born in Makassar, living in Bali and Makassar, with a Javanese grandfather and a Moluccan grandmother. Or born and living in the Netherlands with a Moluccan father and a Toradja mother (Sulawesi). Or, born on Run, study in Jakarta, living on Banda Neira, Grandmother East Java, grandfather Sulawesi, mother West Sumatra, father Banda Neira.

Christian, Portuguese or Dutch surnames, to be found among the Moluccans in the Netherlands, Indonesia and Banda, also indicate interracial marriages.

What is striking about these interracial marriages is that especially the mothers come from non-Moluccan islands. This is due to the fact that the Moluccan men conducted regional and later national trade, were deployed by the Netherlands in the colonial era during internal (Indonesia) wars or were moved from one place to another as slaves, or had temporary work on other islands. from the Indonesian archipelago. And, at the insistence of the Dutch governments, the Dutch colonial men often took a Nai (concubine) who in some cases became wives. From these marital and non-marital unions children were born, whether recognized or not.

What fascinates me is the exchange and mixing of cultural customs, traditions, oral history and even religion. I cannot help feeling that there is more that unites us all than what divides us. However, discovering what binds us requires curiosity, openness, sharing experiences, knowledge, wisdom, insight and customs and an unbiased attitude.

Juul Sadée, December 2020

Kontak dan interaksi lintas budaya.

by Juul Sadée

Siapakah penduduk Banda? Apa budaya khas Banda?

Hal ini mengingat sejak tahun 500 Masehi sudah ada hubungan regional antara pulau-pulau di Tenggara dan Kepulauan Maluku Barat Daya. Tetapi orang Cina juga mengunjungi nusantara pada abad-abad sebelum abad ke-10.

Sejak abad ke-10 dan seterusnya, kontak insidental muncul ketika pedagang dari Jawa dan pulau Sunda Kecil mengunjungi Kepulauan Banda. Ini menciptakan jaringan perdagangan dengan Asia Tenggara.

Orang Turki, Persia, Bengali, Gudjeratis, Cina, Jepang, Melayu, Jawa, Makassar, Ternatan, Tidor, Seram dan pendatang lain dari pulau-pulau yang terletak di sekitar Laut Banda menetap di pemukiman baru di Banda Neira, Banda Besar dan Ay dari abad ke-14. Konflik muncul karena penduduk mapan fokus pada perdagangan rempah-rempah daerah sedangkan pendatang baru melakukan perdagangan nasional.

Pengaruh Eropa datang dengan kunjungan Portugis ke Kepulauan Banda dari awal abad ke-16, diikuti oleh Inggris dan Belanda.

Ketika saya bertanya kepada teman-teman Maluku saya tentang nenek moyang mereka, tempat lahir dan tempat tinggal, jelas terlihat bahwa banyak perkawinan antar ras telah terjadi dengan tempat tinggal yang berbeda-beda di seluruh nusantara. Misalnya, lahir di Makassar, tinggal di Bali dan Makassar, dengan kakek Jawa dan nenek Maluku. Atau lahir dan tinggal di Belanda dengan ayah Maluku dan ibu Toradja (Sulawesi). Atau, lahir di Run, belajar di Jakarta, tinggal di Banda Neira, Nenek Jawa Timur, Kakek Sulawesi, Ibu Sumatera Barat, Ayah Banda Neira.

Nama keluarga Kristen, Portugis atau Belanda, yang dapat ditemukan di antara orang Maluku di Belanda, Indonesia dan Banda, juga menunjukkan perkawinan antar ras.

Hal yang menarik dari pernikahan antar ras ini adalah para ibu yang berasal dari pulau non-Maluku. Hal ini disebabkan oleh fakta bahwa orang-orang Maluku melakukan perdagangan regional dan kemudian nasional, dikerahkan oleh Belanda pada zaman penjajahan selama perang internal (Indonesia) atau dipindahkan dari satu tempat ke tempat lain sebagai budak, atau bekerja sementara di pulau lain. . dari nusantara. Dan, atas desakan pemerintah Belanda, laki-laki kolonial Belanda sering mengambil Nai (selir) yang kadang-kadang menjadi istri. Dari perkawinan dan non-perkawinan anak-anak lahir, disadari atau tidak.

Yang membuat saya terpesona adalah pertukaran dan percampuran adat budaya, tradisi, sejarah lisan, dan bahkan agama. Saya tidak dapat menahan perasaan bahwa ada lebih banyak yang mempersatukan kita semua daripada apa yang memisahkan kita. Namun, menemukan apa yang mengikat kita membutuhkan rasa ingin tahu, keterbukaan, berbagi pengalaman, pengetahuan, kebijaksanaan, wawasan dan adat istiadat serta sikap yang tidak memihak.

Straver, J.A.M.(2018)

Fathers and daughters. Moluccan history in nineteenth-century Dutch literature and its resonance in Indonesia

Doctoral Thesis for Leiden University, the Netherlands

At the end of the eighteenth century the Enlightenment brought forth new ideas on colonial relations and colonial policies. How did these ideas manifest themselves in early nineteenth-century literary fiction?

Vaders en dochters (Fathers and daughters) focusses on three narratives about dramatic events in Moluccan history: a narrative poem by Jan Fredrik Helmers (1812), a short story by Maurits Ver Huell (1837) and a historical novel by Willem Ritter (1844). In all three the main characters are a father and a daughter. These narratives are extensely researched and analyzed. By taking in account more recent historical and antropological findings, an attempt is made to trace the emergence, rise and downfall of Enlightenment idealism in nineteenth-century historical romance.

The stories of Helmers, Ver Huell and Ritter inspired other nineteenth century narratives, both literary and historical. In time some parts were integrated into Bandanese and Ambonese local histories, while the female character of Ver Huells story nowadays is considered a national heroine of Indonesia. In conclusion a postcolonial novel by Y.B. Mangunwijaya, likewise about a father and daughter in the turmoil of Moluccan history, is discussed to highlight the merits and deficiencies of Dutch colonial fiction.

tangan Eva Ment, pasangan J P Coen

“Coen and his time”

by Juul Sadée

In 2013, the book “Coen en his time” by Egbert Ottens was published. A clearly described history of the VOC era with Jan Pieterszoon Coen in the lead role.

In this book, Ottens lays the momentum of history along the yardstick of morality, justice and language. He argues that morality evolves with the times, whereby looking back and judging / condemning is no easy task.

Most surprising is his analysis of Coen’s statement; “Do not dispair, do not spare your enemies.” (dispereert niet, ontsiet uwe vijanden niet’)

This statement was and continues to be regarded as evidence of Coen’s cruelty to this day. However, without questioning Coen’s cruel acts, there is a nuance in the interpretation of this statement.

It “do not dispair, do not spare your enemies” is old Dutch language of the 17th century. Ottens analyzes the word “spare” (ontsiet) by examining its meaning in texts from that time. It turns out that this word does not mean “to spare” but “to fear.” That means that Coen did not mean “do not spare your enemy” or either have no pity or kill them. Coen encouraged his men by addressing them “do not despair, do not fear your enemies,” do not be afraid of them.

This interesting difference in nuance shows once again how meticulous we must be if we are to understand and judge history.

Comparative historical and literature research shows that Coen’s motives were sometimes determined by very crazy events that infuriated Coen, as Muhammad Farid writes in his book “Tana Banda Myth,” historical, social, cultural essays on the island of Banda Naira “. Other social structures and misinterpretations of culturally determined customs and negotiation methods also led to major conflicts.

Juul Sadée, February 19, 2021

Straver, J.A.M.(2018)

Ayah dan anak perempuan. Sejarah Maluku dalam kesusastraan Belanda abad kesembilan belas dan gaungnya di Indonesia

Doctoral Thesis untuk Universitas Leiden, Belanda

Pada akhir abad kedelapan belas Pencerahan melahirkan gagasan baru tentang hubungan kolonial dan kebijakan kolonial. Bagaimana ide-ide ini memanifestasikan dirinya dalam fiksi sastra awal abad kesembilan belas?

Ayah dan anak perempuan berfokus pada tiga narasi tentang peristiwa dramatis dalam sejarah Maluku: puisi naratif karya Jan Fredrik Helmers (1812), cerita pendek karya Maurits Ver Huell (1837), dan novel sejarah karya Willem Ritter (1844). Di ketiga karakter utama adalah ayah dan anak perempuan. Narasi ini diteliti dan dianalisis secara ekstensif. Dengan memperhatikan temuan-temuan sejarah dan antropologis yang lebih mutakhir, dilakukan upaya untuk menelusuri kemunculan, naik turunnya idealisme Pencerahan dalam romansa sejarah abad kesembilan belas.

Kisah Helmers, Ver Huell dan Ritter menginspirasi narasi abad kesembilan belas lainnya, baik sastra maupun sejarah. Belakangan beberapa bagian diintegrasikan ke dalam sejarah lokal Banda dan Ambon, sedangkan tokoh perempuan dalam cerita Ver Huells saat ini dianggap sebagai pahlawan nasional Indonesia. Sebagai kesimpulan, novel pascakolonial oleh Y.B. Mangunwijaya, demikian pula tentang seorang ayah dan anak perempuan dalam gejolak sejarah Maluku, dibahas untuk menyoroti kelebihan dan kekurangan fiksi kolonial Belanda.

“Coen dan waktunya”

by Juul Sadée

Pada 2013, buku “Coen en his time” oleh Egbert Ottens diterbitkan. Sejarah era VOC yang digambarkan dengan jelas dengan Jan Pieterszoon Coen sebagai peran utama.

Dalam buku ini, Ottens meletakkan momentum sejarah di sepanjang tolok ukur moralitas, keadilan, dan bahasa. Dia berpendapat bahwa moralitas berkembang seiring dengan waktu, di mana melihat ke belakang dan menilai / mengutuk bukanlah tugas yang mudah.

Yang paling mengejutkan adalah analisisnya atas pernyataan Coen; “Jangan putus asa, jangan biarkan musuhmu.”( ‘dispereert niet, ontsiet uwe vijanden niet’)

Pernyataan ini dulunya dan terus dianggap sebagai bukti kekejaman Coen hingga hari ini. Namun, tanpa mempertanyakan tindakan kejam Coen, ada nuansa interpretasi atas pernyataan ini.

Itu “jangan putus asa, jangan biarkan musuhmu” adalah bahasa Belanda kuno abad ke-17. Ottens menganalisis kata “cadangan” (ontsiet) dengan memeriksa artinya dalam teks dari waktu itu. Ternyata kata ini tidak berarti “menyayangkan” tapi “takut”. Itu berarti Coen tidak berarti “jangan mengampuni musuhmu” atau tidak mengasihani atau membunuh mereka. Coen mendorong anak buahnya dengan menyapa mereka “jangan putus asa, jangan takut musuhmu”, jangan takut pada mereka.

Perbedaan nuansa yang menarik ini sekali lagi menunjukkan betapa cermatnya kita jika ingin memahami dan menilai sejarah.

Penelitian komparatif sejarah dan literatur menunjukkan bahwa motif Coen terkadang ditentukan oleh peristiwa yang sangat gila yang membuat marah Coen, seperti yang ditulis Muhammad Farid dalam bukunya “Tana Banda Myth,” esai sejarah, sosial, budaya di pulau Banda Naira “. Struktur sosial lainnya dan salah tafsir atas kebiasaan yang ditentukan oleh budaya dan metode negosiasi juga menyebabkan konflik besar.

Juul Sadée, 19 Februari 2021

Women and drums

by Juul Sadée

In the book “When the Drummers Were Women” gives Layne Redmond a wonderful overview of The history of female drummers, from prehistoric times to the present. A number of illustrations show women with the frame drum in their arms with which they played the rhythms of nature, the moon and femimity.

They practiced drumming as a ritual of spiritual awareness. Their rhythms had numerous variations in count that took their playing to great heights.

The book is a tribute to women who showed that the rhythms of drumming are a blessing for body and soul.

Music is one of the components of our interdisciplinary and multi media art project. We are going to work with the Rebana as an accompaniment to the song about a special woman in Banda. The Rebana is a frame drum that is also used on Banda.

The name Rebana came from the Arabic word robbana (“our Lord). She is used in Islamic devotional music in Southeast Asia. The sound of the Rebana often accompany Islamic rituals.

The Rebana existed before Islam came to Indonesia. It is an instrument that has traditionally been played by women, often dancing in a circle.

Juul Sadée, March 2, 2021

Wanita dan genderang

by Juul Sadée

Dalam buku “When the Drummers Were Women” memberikan Layne Redmond gambaran yang indah tentang Sejarah drummer wanita, dari zaman prasejarah hingga saat ini. Sejumlah ilustrasi menunjukkan wanita dengan kerangka drum di lengan mereka yang mereka gunakan untuk memainkan ritme alam, bulan dan feminitas.

Mereka berlatih menabuh sebagai ritual kesadaran spiritual. Irama mereka memiliki banyak variasi hitungan yang membawa permainan mereka ke tingkat yang luar biasa.

Buku tersebut merupakan penghargaan kepada perempuan yang menunjukkan bahwa ritme permainan genderang merupakan berkah bagi jiwa dan raga.

Musik adalah salah satu komponen dari proyek seni interdisipliner dan multi media kami. Kami akan bekerja dengan Rebana sebagai iringan lagu tentang wanita istimewa di Banda. Rebana adalah drum kerangka yang juga digunakan di Banda.

Nama Rebana berasal dari bahasa Arab robbana (“Tuhan kami). Dia digunakan dalam musik devosional Islam di Asia Tenggara. Bunyi rebana sering mengiringi ritual Islam.

Rebana sudah ada sebelum Islam masuk ke Indonesia. Ini adalah alat musik yang secara tradisional dimainkan oleh wanita, sering menari dalam lingkaran.

Juul Sadée, 2 Maret 2021

Pomegranate and Garnet Gemstone

by Juul Sadée

It is said that the first man of Banda arose from the seeds of the pomegranate. The seeds symbolize fertility and vitality on Banda.

The Italian Renaissance artist Sandro Botticelli painted the ‘Madonna with the Pomegranate’ in 1487. Saint Mary has the baby Jesus on her right arm and a pomegranate in her left hand. Mother and child both look sad, a reference to the pain and torture that Jesus faces. The pomegranate seeds therefore refer to the drops of blood of Christ.

In Greek mythology, the pomegranate signified the return of spring. In Islam, eating the fruit would banish hatred and jealousy. The pomegranate tree can become very old and can be up to 8 meters high, it symbolizes strength and the resilience of nature.

The Garnet gemstone owes its name to the pomegranate, due to both its color and the shape of its crystals that resemble the seeds. She has healing powers and symbolizes energy, courage and perseverance. The gemstone is found in India, among other places, and was used as bullets during the Indian revolt against the English in 1857. Due to its high specific gravity, the chunks were quite heavy.

Not only textiles came to Banda via the Silk Road, beads and gemstones such as the Garnet stone were also merchandise that came to Europe via Banda.

Juul Sadée, June 22, 2021

Delima dan Garnet Batu Permata

by Juul Sadée

Dikatakan bahwa manusia pertama Banda muncul dari biji buah delima. Bijinya melambangkan kesuburan dan vitalitas di Banda.

Seniman Renaisans Italia Sandro Botticelli melukis ‘Madonna dengan Buah Delima’ pada tahun 1487. Santa Maria memiliki bayi Yesus di lengan kanannya dan buah delima di tangan kirinya. Ibu dan anak keduanya terlihat sedih, mengacu pada rasa sakit dan siksaan yang dihadapi Yesus. Oleh karena itu, biji delima merujuk pada tetesan darah Kristus.

Dalam mitologi Yunani, buah delima menandakan kembalinya musim semi. Dalam Islam, makan buah akan menghilangkan kebencian dan kecemburuan. Pohon delima bisa menjadi sangat tua dan tingginya bisa mencapai 8 meter, melambangkan kekuatan dan ketahanan alam.

Batu permata Garnet berutang namanya ke buah delima, karena warna dan bentuk kristalnya yang menyerupai biji. Dia memiliki kekuatan penyembuhan dan melambangkan energi, keberanian dan ketekunan. Batu permata itu ditemukan di India, di antara tempat-tempat lain, dan digunakan sebagai peluru selama pemberontakan India melawan Inggris pada tahun 1857. Karena berat jenisnya yang tinggi, bongkahannya cukup berat.

Tidak hanya tekstil yang datang ke Banda melalui Jalur Sutra, manik-manik dan batu permata seperti batu Garnet juga merupakan barang dagangan yang datang ke Eropa melalui Banda.

Juul Sadée, 22 Juni, 2021

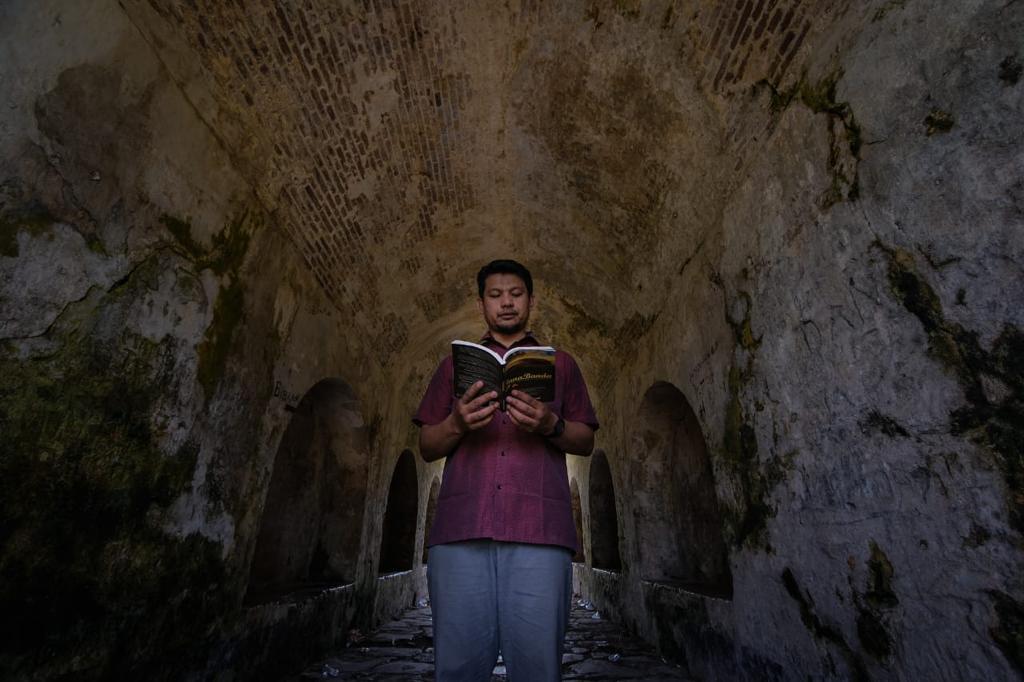

‘Tana Banda Myth’, historical, social, cultural essays about the island of Banda Neira, in the hallway of Fort Nassau on Banda Neira.

Photo Rahmad Ladae 2020

Commemorating the Banda Genocide in 1621; for what and who?

by Dr. Muhammad Farid

Lecturer in Social History, Head of Hatta-Sjahrir College-Banda Naira

08-05-2021

“Dispereert niet, onziet uw vijanden niet, want god is met ons “, may be the motto of the most violent life in the history of humanity. The motto became Jan Pieterszoon Coen’s life principle when he conquered Banda, long before Der Fuhrer Hitler destroyed Europe, or Pol Pot danced over the killing fields of Cambodian civilians.

Dispereert niet … and so on, means “Don’t give up, don’t be afraid of your enemies, because God is with us” at first sounds like an ordinary motivational sentence. But anyone who reads Banda history and knows what Coen had done there will affirm that this sentence has been the most sadistic mantra of all ages.

But Coen was not a soldier. He started his career as a junior trader. Another version says he was a clerk of his superior, Pieter Willemszoon Verhoeff (1573–1609), a disciplined admiral and risk decision maker. One of his controversial decisions was when he built a VOC fortress in Banda. Verhoeff argued, the fort was built for the purpose of “protecting their property” from the Portuguese and British, and at the same time to protect Banda. But Banda’s figures from the start refused because they thought it was just a trick. However, the Banda people did not have the strength in the face of the Verhoeven army. Some of them even fled to the hills out of fear.

In the end, the Banda leaders agreed to send envoys for a peace negotiation. Verhoeven had suspected that this was the only option the Banda people should take rather than fought him. He also agreed to the negotiations by bringing along a board of captains, traders, and a troop of fully armed soldiers. But unexpectedly, he was killed in a trap. Vincenth Loth (1995) in his article entitled Pioneers & Perkeniers, mentions that the killing of Verhoeff and 46 soldiers by the Banda people at that time was a “disturbance” of the diplomatic mission for the first time in VOC history. Verhoeven’s death hit the morale of his troops. Reportedly spread in almost all the port capitals of the VOC colonies, from Tuban, Gresik, Palembang, the Bay of Bengal, Malacca, Calcutta, and Sri Lanka.

Jan Pieterszoon Coen was a living witness to Verhoeff’s death. He certainly kept the traumatic event deep, while nurturing his ambitions for the future. His expertise later attracted VOC directors, making him the Governor-General of the VOC at a young age, 31 years old!

When he was in power, Coen showed his true behavior. His decision to move the VOC trading office from Banten to the Jayakarta area was proof of his intense hatred towards the British and also the people of Banten. He then built up his military defenses, then launched sporadic attacks on British fortifications and the Javanese Palace (Mataram Kingdom). The victory was achieved perfectly. From the ruins of the city of Jayakarta, he built a new city called “Batavieren” (now Jakarta).

After the destruction of Java, Coen turned his attention back to Banda Naira. For Coen, the spice island had to be conquered only by military force, and its stubborn people had to be destroyed or banished. This principle is in accordance with the suggestion from L’Hermite de Jonge to Heeren XVII quoted by van de Wall (1934) in Bijdrage tot de geschiedenis der Perkeniers 1621-1671, that;

“The most effective way to get the nutmeg monopoly is to destroy the ‘disturbing’ population and replenish the islands with invaders to be served by slaves”.

J.P Coen firmly believed that the failure of the VOC predecessors in Banda Naira was actually because they did not have 3 principles; “Strong motivation, efficiency, and ruthlessness”. He always addressed these three principles in front of VOC officials in the Netherlands, and were actually manifested in Banda Naira.

Genocide 1621

Des Alwi (2007) in his book, Sejarah Banda Naira, records the first landing of the J.P.Coen war fleet on 27 February 1621 at Fort Nassau. Together with his military forces consisting of 13 large ships, 3 small ships, 6 sailboats, with an army of 1,665 Europeans, plus 250 soldiers who had settled in Banda, 100 mercenaries from the ronin-samurai troops, and 286 prisoners from Java as a ship worker.

On March 4 and 5, 1621, Coen instructed the Het Hert Ship to sail around Banda Besar and scouted the Lonthoir coast. During the reconnaissance mission, the Het Hert received repeated fire from various parts of the island. His troops suffered defeat, as many as 2 crew members were killed and 10 soldiers were injured. The VOC troops lost and withdrew slowly. But the reports that had entered Coen’s table were far more important than that momentary defeat. He was fortunate to obtain data that there were a dozen indigenous defenses scattered from the coast to the southern ridges of the island of Lonthoir. He also captured some of the activity of native troops who were trained by British soldiers in simple military camps.

In the second attack on March 11, 1621, Coen’s troops were more strategic by deploying troops at 6 points at once to trick the people of Banda. In a short time, VOC forces occupied important posts to the north near Ortatang and to the south near Lakoy. Despite the fierce resistance of the Banda people, in the end most of Banda Besar was conquered even before sunset. The local historian, Des Alwi, noted the treacherous act of the Lakoy and Ortatang residents who gave way to the pockets of the people’s army for only 30 rials.

This unfortunate situation made one of the Orang Kaya (OK) Lonthoirs named Kalabaka Maniasa try to diplomacy with Coen on his boat. Kalabaka was a Banda-Dutch crossbreed who was intelligent, brave and fluent in Dutch. Kalabaka had a nickname, Yongheer Dirk Callenbacker. Dealing with Coen, Kalabaka got into an argument because Coen accused him of being the mastermind of the trouble; broke trade promises, and even killed many Dutch merchants. Kalabaka denied. He instead blamed the Dutch for being cruel and greedy. The debate was deadlocked.

Coen continued to carry out attacks and raids on people’s defense centers. This made the OKs and the Banda religious leaders finally gave up. They came to Coen on his ship with tribute from the nutmeg harvest, some of them carrying copper kettles, chains of gold, and handing over weapons. They also promised to repatriate some of the residents who were still hiding in the forests and mountains, and also obeyed all trade agreements that were enacted. They only asked the VOC 4 conditions; to respect their property, family, and religion.

Coen accepted the surrender of the Banda people happily without the slightest concern for their requests. The surrender of the Banda leaders further smoothed Coen’s grand plan; conquest!

Coen’s desire to conquer Banda was actually a continuation of the attitude of his predecessors, especially Simon Janszoon Hoen, replacing Verhoef, who loudly declared war on Banda and his allies in order to avenge the murder of its leader. For Hoen, colonizing Banda was a must. This claim, according to van Ittersum (2016) in his writing entitled, Debating Natural Law in the Banda Islands, further sparked the idea of Jus Conquestus, or “legitimate occupation” in the colonial era law of war.

With this “Jus Conquestus” claim, Coen reluctantly built a solid fortress at the top of Lonthoir, established his headquarters in Selamon, issued controversial policies such as appointing the native Jareng as OK, and positioning General T’Sionck as the new governor. Even though these two persons were very disliked by the residents of Banda and the Netherlands themselves. Jareng was considered a traitor to the Banda people. Meanwhile, T’Sionck was known as a drunkard, clumsy, and ignorant.

One of T’Sionck’s ignorance was to make the old mosque in Selamon as a bedroom for soldiers, to turn people’s houses into warehouses for booty, and also to insult Banda women who were forcibly gathered to groom in front of VOC soldiers. The people of Banda Naira repeatedly begged not to do this, but the governor did not care.

The night of April 21, 1621, thick black clouds covered the Banda sky as black as the hearts and minds of the people of Banda. At one time, a pendant lamp suddenly fell from the ceiling of the mosque and hit the sleeping Dutch troops. The soldiers hurriedly got up, including T’Sionck who immediately ordered full alert. T’Sionck accused this was a conspiracy to kill him. He ran out of the mosque and became furious while spewing bullets in all directions, waking up the people of Selamon who were running in fear.

The Selamon mosque incident was heard as a rebellion movement by the Banda people against the VOC to Coen’s ears. He became furious and immediately ordered the forced arrest of all the residents who had fled to the forests. The version of T’Sionck’s story was completely swallowed up by Coen without checking the truth. J.A. van der Chijs (1886) in De vestiging van het Nederlandsch gezag over de Banda eilanden, 1599-1621 met een kaart, cites the allegations of the Banda rebellion against the VOC at the end of April 1621 as the alibi Coen needed to initiate a counterattack; as justification for his evil plans in the future.

The hunting of the natives was sporadic and cruel. Residents who resisted were immediately killed. Vincent Loth (1995) mentions a large group of desperate men, women and children who jumped off the cliffs of Selamon and Lonthoir. Others chose to survive despite hunger rather than surrender. And only a few managed to make boats to escape at night to the Kai Islands, Seramlaut, Kisar, and other small islands in the Gorom Archipelago.

Those who were arrested were then tortured on a torture chair that crushed the bones of the legs and arms in one turn. Others were tortured by tying their legs with ropes to four horses, which when the horses were whipped could sever the bodies of the prisoners with a single whip.

Of all the atrocities committed by Coen throughout 1621, there was one incident that has caught the world’s attention, and at the same time drained the heart and feelings of anyone who reads the history of VOC colonialism in East India. The report was written by J.A Chijs 50 years later after the VOC dissolved.

It occurred on May 8, 1621, after almost a month of hunting for Banda residents, Coen managed to gather as many as 44 Orang Kaya (some versions mention 48 people) who were considered the most dangerous and were accused of being the mastermind of treason against the colonialists. The OKs were then herded like sheep into a circular bamboo fence outside the fort of Nassau. Under the pouring rain a soldier read out mistakes they had never done. Then the ronin butchers who were ready to swing the samurai immediately executed it without mercy. First, the eight most important figures were chopped up in half, then cut off their heads. After that, the ronin split their bodies into four parts. The part of the head that has been severed is then plugged into the ends of the bamboo. The fate of the other 36 OK experienced the same thing. The OKs were killed without a word spoken, except for one of them asked softly; “Don’t you feel sinned?”

After the genocide, Banda was hit by torrential rains for up to 3 months. Nature seemed to be crying over the death of the warriors of the land of Banda. But Coen was numb. He didn’t seem the slightest bit sorry. He even celebrated the event with a banquet with his troops on May 15, 1621. The banquet was also a moment of his farewell with the VOC soldiers in Nassau fortress. For Banda people, genocide was the deepest wound. But for Coen, he was just doing duty of the State.

Banda after Coen: A Memmoria In Passionis

Banda was like a dead city. “There is nothing left”, wrote Eduard Douwes Dekker, whose pseudonym Multatuli, when he wrote about the Banda genocide in 1621. However, several other historical sources mention that of the 15,000 inhabitants of Banda before the genocide, now only 1000 people live on the islands of Naira and Banda Besar, excluding Ai and Rhun, which have a population of about several hundred people who were not disturbed by British rule on the two islands. Meanwhile, the small inhabitants who inhabit Rosingain Island were deported to the main islands and then spread to nutmeg plantations into forced labor. And as many as 789 people consisting of male and female parents, as well as children who were banished to Batavia as slaves, and some others ended up in Sri Lanka.

After Coen, Banda was only inhabited by the majority of mothers and daughters. Leaving several settlements empty. Some of them; 1800 huts in the hills of Selamon (Banda Besar), more than 700 graves around it, and 9 bodies that have not been buried. Mount Wayer also found 1000 huts and several graves.

Banda increasingly drowned in silence and lamentation. Coen’s cruelty made an impression on the wounded memory. Become a “memmoria in passionis” or experience suffering for the brutality they experienced. The black memory left on the names of the villages in the city of Neira to this day such as; “Coen village”, and “village Parhopen”. A traumatic memory.

Some of the memories are immortalized in poems longing for the land of Banda and the ancestors who were killed. The poem is known as Onottan Syarawandan, which has been spoken from generation to generation. Believed to be the truth by those who chose to migrate to leave Banda Naira who later called themselves “orang Wandan “.

For the rest of the population living in Banda, these memories are immortalized in meaningful dances. Known as “Cakalele Banda”. A unique dance movement that combines aesthetic and political values. Aesthetic because it is packaged in the art of dance, political because it contains the meaning of resistance as well as respect for the ancestors who were killed without justice. In Cakalele, there is an important message that the ancestors did not die in vain, but died as knights.

Commemorating the Genocide for What and Who?

After the Banda genosda, Jan Pieterszoon Coen headed for Jakarta and arrived on 12 July. He was greeted with great fanfare like a successful hero with a procession of cannon fire from land and sea. Coen was even rewarded with 3000 guilders with a slight administrative penalty. The price of the Conquest of Banda by Coen was fantastic; The VOC was able to build the city of Amsterdam, Hoorn, and a number of strong fortresses in Batavia.

In my opinion, this historical fact should be opened to the public as widely as possible, and must not be covered up. Let everyone know that colonial policy was so vulgar that it paid a small price for the lives of its colonists with money, feasts, and honor. The cruelty that became “Banal”. An injustice that is celebrated.

Answering the question, why commemorate the Banda 1621 genocide? Of course, in my mind, is for a more objective historical writing for a better common future. We need to start a historiography that is fair, honest and open. Completely write down who Verhoeff really was, and describe who Jan Pieterszoon Coen really was.

I certainly appreciate the iconoclasm that has emerged in recent years in the Netherlands, where there have been mass protests against symbols of colonialism in the public sphere. Like the statue of Coen in the city of Hoorn, which was once revered as a hero but has now turned into a target of mob fury.

According to the article by Joella van Dongkersgoed (2019), the public debate about J.P. Coen has been getting higher since early 2018, triggered by the removal of a replica statue of Maurits van Nassau from Mauritshuis in The Hague and the initiative to change the name of an elementary school named Jan Pieterszoon Coen-school in an “Indonesian” neighborhood in Amsterdam.

I understand the phenomenon that the Dutch newspapers call the “Nieuwe Beelden Storm” as a new historical awareness that is growing in the lives of Dutch citizens. Within that new awareness there was a desire to rewrite the history of their lives for a better future.

Of course I personally prefer to advise Dutch citizens to be wiser towards colonial symbols, by treating them fairly, honestly and openly, rather than making them a target of vandalism, or even destroying them.

One of the wise ways is to start a historiography that is fair and honest so that we can put the thoughts and feelings of the colonial icons in the right place. Thus, although the statue of Jan Pieterszoon Coen still stands firmly in the city of Hoorn to this day, through this “historical honesty” anyone will still smell the stench of the blood of the Banda people all over Coen’s body

***

Then, for whom is the Banda genocide commemorated? Of course for all of us who claim to be a civilized nation. For the Dutch, this genocide is impossible to deny. No matter how much legitimacy the justification of past brutality is sought, it will be futile. Meanwhile, for the Bandanese, this genocide cannot possibly be erased from our memory. No matter how strong the memories are erased, they will remain attached. So the best attitude is “forgive but never forget” (forgiven but not forgotten). This means that commemorating the genocide for the Dutch is solely for the purpose of building a harmonious mutual relations in the future. Meanwhile, for the people of Banda, this commemoration will become a reflection of their life to love and protect Banda more for a better future.

“Guarding Banda” is the key word. This island of spices was once ravaged by arrogance, greed and tyranny. The land was seized, the palms were burned, the women were harassed, the people were evicted and even slaughtered without mercy. Today, this brutality can be repeated, by anyone, by any nation, even by the people of Banda themselves!

So the Banda Genocide must be the momentum for mutual awakening. The commemoration of genocide needs to be carried out continuously in order to foster a spirit of togetherness to protect the homeland of Banda Naira. Didn’t historical facts prove that the VOC’s cruelty towards the Banda people was also caused by the internal division of the Banda people? Didn’t the conquest come about as a result of betrayal by the Banda people themselves?

The plurality of Banda is a priceless wealth. Ethnic and cultural diversity is a gift from God to be grateful for. So the VOC’s past project of ethnic cleansing of Banda with the aim of re-transforming the Banda population according to colonialist interests was actually a historical error. Banda today has become so diverse and rich. Ethnic, cultural, and religious diversity not make them live separately in claims of group superiority, but instead still recognize themselves as one common community.

The profile of the Banda people is a good example for a pluralistic Indonesia. If Indonesia today is still in the process of becoming a nation, Banda today has finished with it all. Banda has become the ideal type for a plural society living together in a unified ethnicity, which we call, “Banda people”!

Reference

Alwi, Des. 2007. Muhammad Farid (ed.). Sejarah Banda Naira. Pustaka Bayan, Malang

Chijs, J.A. van der. 1886. De vestiging van het Nederlandsch gezag over de Banda eilanden, 1599-1621 met een kaart. Batavia: Bataviaasch Genootschap van Kunsten en Wetenschappen

Farid, Muhammad. 2020. TanaBanda: Essai-essai tentang Mitos, Sejarah, Sosial, Budaya Pulau Banda Naira. Sintesa Book, CV. Sintesa Prophetica

Lape, Peter V. 2000. Political Dynamics and Religious Change in the Late Pre-Colonial Banda Islands, Eastern Indonesia. Archeology in Southeast Asia, Vol.32, p.138-155. Taylor & Francis Ltd.

Loth, Vincent C., 1995. Pinoneers and Perkeniers: The Banda Islands in The 17th Century. Cakalele, vol.6, pp.13-35.

Van den Berg. 1995: 13 Berg, Joop van den. 1995. Het verloren volk; Een geschiedenis van de Banda-eilanden.’s-Gravenhage: BZZTôH.

© Westfries Museum 2021

Memperingati Genosida Banda tahun 1621; untuk apa dan siapa?

oleh Dr. Muhammad Farid

Dosen Sejarah Sosial, Kepala Sekolah Hatta-Sjahrir-Banda Naira

08-05-2021

Dispereert niet, onziet uw vijanden niet, want god is met ons”, boleh jadi adalah moto hidup paling bengis sepanjang sejarah kemanusiaan. Moto itu menjadi prinsip hidup Jan Pieterszoon Coen saat menaklukan Banda, jauh sebelum Der Fuhrer Hitler memporak-pondakan Eropa, atau Pol Pot yang berdansa di atas ladang pembantaian warga sipil Kamboja. Dispereert niet… artinya “Jangan berputus asa, jangan takut musuhmu, karena Tuhan bersama kita”, sepintas tampak sebagai kalimat motivasi biasa. Tapi siapapun yang membaca sejarah Banda dan tahu apa yang dilakukan Coen disana akan mengafirmasi bahwa kalimat itu bagaikan mantra paling sadis sepanjang abad.

Tapi Coen bukan seorang prajurit perang. Dia mengawali karirnya sebagai pedagang junior. Versi lain menyebutkan dia pernah menjadi juru tulis atasannya, Pieter Willemszoon Verhoeff (1573–1609), seorang Laksamana yang disiplin dan pengambil keputusan berisiko. Salah satu keputusan kontroversial adalah membangun benteng VOC di Banda. Verhoeff berdalih, benteng dibangun untuk tujuan “menjaga milik mereka” dari Portugis dan Inggris, dan sekaligus untuk menjaga Banda. Tapi para tokoh Banda sejak awal menolak karena menganggap itu hanyalah muslihat belaka. Namun demikian, orang Banda tidak memilik kekuatan dihadapan pasukan tentara Verhoeven. Sebagian mereka bahkan melarikan diri ke bukit-bukit karena takut.

Pada akhirnya para tokoh Banda bersepakat mengirim utusan untuk sebuah perundingan damai. Verhoeff sudah menduga itulah satu-satunya pilihan yang harus diambil orang Banda daripada melawannya. Dia pun menyetujui perundingan itu dengan membawa serta para dewan Kapten, para pedagang, dan sepasukan tentara bersenjata lengkap. Namun tanpa disangka, dia mati terbunuh dalam jebakan. Vincenth Loth (1995) dalam artikelnya berjudul Pioneers & Perkeniers, menyebutkan terbunuhnya Verhoeff bersama 46 serdadu oleh orang Banda saat itu merupakan “gangguan” misi diplomatik pertama kali dalam sejarah VOC. Kematian Verhoeff sangat memukul moral pasukannya. Beritanya tersebar hampir di seluruh ibukota pelabuhan koloni VOC, dari Tuban, Gresik, Palembang, Teluk Benggala, Malaka, Kalkuta, dan Srilanka.

Jan Pieterszoon Coen adalah saksi hidup kematian Verhoeff. Sudah tentu dia menyimpan dalam-dalam peristiwa traumatik itu, sambil memupuk ambisinya di masa depan. Setelah memikat hati para direktur VOC, Coen didaulat menjadi Gubernur Jendral VOC di usianya yang masih muda, 31 tahun!

Saat berkuasa, Coen menunjukkan watak aslinya. Keputusannya memindahkan kantor dagang VOC dari Banten ke wilayah Jayakarta adalah salah satu bukti kebenciannya yang teramat sangat terhadap Inggris dan juga warga pribumi (Banten). Dia kemudian membangun kokoh pertahanan militernya, lalu melancarkan serangan-serangan sporadic ke benteng-benteng pertahanan Inggris dan Istana Jawa (Kerajaan Mataram). Kemenangan diraihnya dengan sempurna. Dari atas puing-puing kota Jayakarta, Coen membangun kota baru yang dinamainya “Batavieren” atau Batavia (sekarang Jakarta).

Pasca penghancuran tanah jawa, Coen mengarahkan perhatiannya kembali ke Banda Naira. Wilayah yang menyimpan dendam lamanya. Bagi Coen, pulau subur dan wangi itu harus ditaklukkan hanya dengan kekuatan militer, dan masyarakatnya yang keras kepala harus dibinasakan atau dibuang. Prinsip itu sesuai dengan saran dari L’Hermite de Jonge kepada Heeren XVII yang dikutip van de Wall (1934) dalam Bijdrage tot de geschiedenis der Perkeniers 1621-1671, bahwa

“cara paling efektif untuk mendapatkan monopoli pala adalah dengan menghancurkan populasi yang ‘mengganggu’ dan mengisi kembali pulau-pulau dengan penjajah yang akan dilayani oleh budak”.

J.P. Coen sangat yakin bahwa kegagalan para pendahulu VOC di Banda Naira sesungguhnya karena mereka tidak memiliki 3 prinsip; “motivasi yang kuat, efisiensi, dan kebengisan”. Tiga prinsip ini selalu dia pidatokan di depan para petinggi VOC di Belanda, dan benar-benar diwujudkannya di Banda Naira.

Genosida 1621

Des Alwi (2007) dalam bukunya, Sejarah Banda Naira, mencatat pendaratan pertama armada perang J.P.Coen pada 27 Februari 1621 di Benteng Nassau. Bersama pasukan militernya yang terdiri dari 13 kapal besar, 3 kapal kecil, 6 perahu layar, dengan pasukan tentara sebanyak 1.665 orang eropa, ditambah 250 tentara yang telah menetap di Banda, 100 orang tentara bayaran dari pasukan ronin-samurai, dan 286 tawanan asal Jawa sebagai buruh kapal.

Keterangan yang sedikit berbeda dari versi Loth (1995) dalam tulisannya, Pioneers and perkeniers: The banda islands in the 17th century, yang menyebutkan armada kapal Coen sejumlah 19 kapal yang diawaki oleh 1.655 tentara Eropa, 286 pasukan Asia, dan kontingen pasukan lokal Banda dengan armada sebanyak 36 kapal.

Tepat pada tanggal 4 dan 5 Maret 1621, Coen menginstruksikan Kapal Het Hert berlayar mengitari Banda Besar dan mengintai pesisir Lonthoir. Dalam misi pengintaian itu, kapal Het Hert menerima tembakan bertubi-tubi dari berbagai penjuru pulau. Pasukannya menderita kekalahan, sebanyak 2 awak tewas dan 10 tentara luka-luka. Pasukan VOC kalah dan mundur perlahan. Namun laporan yang masuk ke meja Coen jauh lebih penting dari kekalahan sesaat itu. Dia beruntung memperoleh data bahwa ada selusin titik pertahanan pribumi yang tersebar dari pesisir pantai sampai di punggung-punggung bukit bagian selatan pulau Lonthoir. Dia juga menangkap beberapa aktivitas pasukan pribumi yang dilatih tentara Inggris di kamp-kamp militer sederhana.

Dalam serangan kedua pada 11 Maret 1621, pasukan Coen lebih strategis dengan menerjunkan tentara pada 6 titik sekaligus untuk mengelabui rakyat Banda. Dalam waktu singkat, pasukan VOC telah menduduki pos-pos penting di sebelah utara dekat Ortatang dan sebelah selatan dekat Lakoy. Meskipun mendapat perlawanan sengit rakyat Banda, namun akhirnya hampir seluruh Banda Besar dapat ditaklukan bahkan sebelum matahari terbenam. Sejarawan local, Des Alwi, mencatat tindakan pengkhianatan oknum warga Lakoy dan Ortatang yang memberi jalan ke kantong-kantong tentara rakyat hanya demi 30 real.

Situasi yang semakin tidak menguntungkan membuat salah satu Orang Kaya (OK) Lonthoir bernama Kalabaka Maniasa mencoba berdiplomasi dengan Coen di atas kapalnya. Kalabaka adalah seorang peranakan belanda-banda yang cerdas, pemberani dan sangat fasih berbahasa Belanda. Kalabaka memiliki nama panggilan, Yongheer Dirk Callenbacker. Berhadapan dengan Coen, Kalabaka terlibat adu mulut karena Coen menuuduhnya sebagai biang kerok masalah; melanggar janji-janji perdagangan, dan bahkan banyak membunuh pedagang Belanda. Kalabaka membantah. Dia justru menyalahkan Belanda yang berlaku kejam dan serakah. Debat berujung buntu.

Coen terus melakukan penyerangan dan penyergapan ke sentra-sentra pertahanan rakyat. Hal itu membuat para OK dan pemuka agama Banda akhirnya menyerah. Mereka mendatangi Coen di atas kapalnya dengan membawa serta upeti dari hasil panen pala, sebagian membawa ceret tembaga, rantai dari emas, dan menyerahkan senjata-senjata. Mereka juga berjanji memulangkan sebagian warga yang masih bersembunyi di hutan dan pegunungan, juga menaati semua kesepakatan dagang yang diberlakukan. Mereka hanya meminta 4 syarat kepada VOC; untuk menghormati hak milik mereka, keluarga, dan agama.

Coen menerima penyerahan rakyat Banda dengan gembira tanpa sedikitpun perduli dengan permintaan yang diajukan. Kekalahan Banda semakin memuluskan rencana besar Coen; penjajahan!

Nafsu Coen untuk menaklukkan Banda sejatinya adalah kelanjutan sikap pendahulunya, terutama Simon Janszoon Hoen pengganti Verhoef yang dengan lantang menyatakan perang terhadap Banda dan sekutunya demi membalas pembunuhan pemimpinnya. Bagi Hoen, menjajah Banda adalah keharusan. Klaim ini menurut van Ittersum (2016) dalam tulisannya berjudul, Debating Natural Law in the Banda Islands, selanjutnya memicu gagasan Jus Conquestus, atau “penjajahan yang sah” dalam hukum perang era kolonial.

Dengan klaim “penjajahan yang sah” itulah Coen tanpa segan membangun benteng kokoh di puncak Lonthoir, mendirikan markas besarnya di Selamon, mengeluarkan kebijakan-kebijakan kontroversial seperti mengangkat pribumi Jareng sebagai OK, dan memposisikan Jenderal T’Sionck sebagai Gubernur baru. Padahal dua orang ini sangat tidak disukai penduduk Banda dan Belanda sendiri. Jareng dianggap sebagai pengkhianat orang Banda. Sementara T’Sionck dikenal sebagai pemabuk, ceroboh, dan dungu.

Salah satu kecerobohan T’Sionck adalah menjadikan masjid tua di Selamon sebagai kamar tidur serdadu, merubah rumah-rumah warga menjadi gudang dan akomodasi harta rampasan, juga melakukan penistaan terhadap perempuan-perempuan Banda yang dikumpulkan paksa untuk bersolek di depan serdadu VOC. Penduduk Banda Naira berulang kali memohon untuk tidak melakukan hal itu, namun sang Gubernur tidak perduli.

Malam hari tanggal 21 April 1621, awan pekat menyelimuti langit banda sepekat hati dan pikiran warga Banda. Suatu ketika, sebuah lampu gantung tiba-tiba jatuh dari langit-langit masjid menimpa pasukan Belanda yang sedang tidur. Para serdadu bergegas bangun, termasuk T’Sionck yang langsung memerintahkan siaga penuh. T’Sionck menuduh ini sebuah konspirasi membunuh dirinya. Dia berlari keluar masjid dan menjadi kalap sambil memuntahkan peluru kesegala arah sehingga membangunkan warga Selamon yang berlari ketakutan.

Peristiwa masjid Selamon terdengar sebagai gerakan pemberontakan warga Banda terhadap VOC bagi telinga Coen. Dia naik pitam dan langsung memerintahkan penangkapan paksa terhadap semua warga yang telah melarikan diri ke hutan-hutan. Versi cerita T’Sionck ditelan mentah-mentah oleh Coen tanpa terlebih dahulu mengecek kebenaran sesungguhnya. J.A. van der Chijs (1886) dalam De vestiging van het Nederlandsch gezag over de Banda eilanden, 1599-1621 met een kaart, menyebutkan tuduhan pemberontakan warga Banda terhadap VOC di akhir April 1621 itu sebagai alibi yang dibutuhkan Coen untuk memulai serangan balik; sebagai justifikasi rencana-rencana jahatnya di kemudian hari.

Pengejaran terhadap penduduk pribumi dilakukan secara sporadic dan kejam. Warga yang melawan langsung dibunuh ditempat. Vincent Loth (1995) menyebutkan ada sekelompok besar pria, wanita, dan anak-anak yang putus asa lalu melompat dari tebing-tebing Selamon dan Lonthoir. Sebagian lain memilih bertahan meski kelaparan daripada menyerah. Dan hanya sedikit yang berhasil membuat perahu untuk melarikan diri pada malam hari ke Kepulauan Kai, Seramlaut, Kisar, dan pulau-pulau kecil lainnya di Kepulauan Gorom.

Tapi bagi mereka yang tidak sempat menyelamatkan diri langsung ditangkap dan disiksa di atas kursi penyiksaan yang mampu membuat tulang-tulang kaki dan tangan remuk dengan satu kali putaran. Beberapa lainnya disiksa dengan mengikat kaki-tangan dengan tali pada empat ekor kuda yang ketika kuda-kuda itu dipecut dapat memutuskan tubuh-tubuh tawanan itu dengan sekali pecutan.

Dari semua kekejaman yang dilakukan Coen sepanjang 1621, ada satu kejadian yang paling menyita perhatian dunia, sekaligus menguras hati dan perasaan siapapun pembaca sejarah kolonial VOC di tanah air. Laporan itu ditulis J.A Chijs 50 tahun kemudian setelah VOC bubar.

Terjadi pada 8 Mei 1621, setelah hampir satu bulan pengejaran dilakukan, Coen berhasil mengumpulkan sebanyak 44 Orang Kaya (beberapa versi menyebutkan 48 orang) yang dianggap paling berbahaya dan dituduh sebagai otak dari upaya makar terhadap kolonial. Para tokoh kemudian digiring layaknya domba-domba kedalam sebuah pagar bambu yang melingkar di luar benteng Nassau. Dibawah kucuran hujan deras kesalahan-kesalahan yang tidak pernah mereka lakukan itu dibacakan. Lalu para jagal ronin mengayunkan samurai mengksekusi tanpa belas kasihan. Pertama delapan tokoh terpenting yang dipotong tubuh sampai terbelah dua, baru kemudian memenggal kepala mereka. Tidak berhenti sampai disitu, para ronin kemudian membelah badan mereka menjadi empat bagian. Sementara kepala yang sudah terpenggal lalu ditancapkan di ujung-ujung bambu. Nasib 36 OK lainnya mengalami hal serupa. Para OK terbunuh tanpa satu kata pun terucap, kecuali seorang diantara mereka bertanya lirih; “apakah tuan-tuan tidak merasa berdosa?”

Pasca pembantaian Coen, Banda diguyur hujan lebat sampai 3 bulan lamanya. Tampak alam ikut menangisi kepergian para pejuang tanah banda. Tapi Coen mati rasa. Tak tampak sedikitpun penyesalan dirinya, yang justru merayakan peristiwa itu dengan jamuan makan bersama pasukannya pada 15 Mei 1621. Jamuan makan itu sekaligus moment perpisahannya bersama tentara VOC di benteng Nassau. Bagi rakyat Banda, peristiwa itu adalah luka terdalam, tapi bagi Coen, dia hanya melakukan tugas Negara.

Banda Pasca Coen: Sebuah memmoria in passionis

Banda seperti kota mati. “Tidak ada yang tersisa”, begitu tulis Eduard Douwes Dekker, yang bernama samaran Multatuli, ketika dia menulis tentang genosida Banda tahun 1621. Namun beberapa sumber historis lain menyebutkan dari 15.000 penduduk Banda sebelum genosida, yang tersisa hanya 1000 orang yang mendiami pulau Naira dan Banda Besar, tidak termasuk Ai dan Rhun yang berpenduduk sekitar beberapa ratus orang yang tidak terganggu akibat penguasaan Inggris di kedua pulau itu. Sementara penduduk kecil yang mendiami pulau Rosingain dideportasi ke pulau-pulau utama dan kemudian disebarkan ke perkebunan pala menjadi pekerja paksa. Dan sebanyak 789 orang terdiri dari orang tua laki-laki dan wanita, juga anak-anak dibuang ke Batavia sebagai budak, dan sebagian lain berakhir di Srilanka.

Setelah Coen, Banda hanya dihuni oleh mayoritas para ibu dan anak-anak perempuan. Menyisakan beberapa perkampungan kosong. Antara lain; 1800 gubuk di perbukitan Selamon (Banda Besar), lebih dari 700 kuburan di sekitarnya, dan 9 mayat yang belum sempat dikuburkan. Di Gunung Wayer juga ditemukan 1000 gubuk dan beberapa kuburan.

Banda semakin tenggelam dalam kesunyian dan ratapan. Kekejaman Coen membekas dalam ingatan yang terluka. Menjadi sebuah “memmoria in passionis” atau pengalaman penderitaan atas kebrutalan yang mereka alami. Memori hitam itu meninggalkan pada nama-nama kampong di kota Neira sampai hari ini seperti; “kampong Coen”, dan “kampong Parhopen”. Sebuah kenangan traumatik.

Sebagian memori abadi dalam syair-syair kerinduan terhadap tanah Banda dan para leluhur yang terbunuh tanpa keadilan. Syair itu dikenal dengan nama Onottan Syarawandan, yang dituturkan secara lisan turun-temurun. Diyakini sebagai suatu kebenaran oleh mereka yang memilih hijrah meninggalkan Banda Naira yang kemudian menyebut dirinya sebagai “orang Wandan”.

Bagi mereka yang tersisa di Banda, kenangan itu diabadikan dalam tarian-tarian yang sarat makna. Dikenal dengan nama “Cakalele Banda”. Sebuah gerak tarian unik yang memadukan nilai estetis sekaligus politis. Estetis karena dikemas dalam seni tari, politis karena mengandung makna perlawanan sekaligus penghormatan kepada para leluhur yang terbunuh tanpa keadilan. Dalam Cakalele, terkandung pesan penting bahwa para leluhur tidaklah mati sia-sia, tetapi mati sebagai kesatria.

“Truestoriografi”: Menuju Penulisan Sejarah yang jujur dan adil.

Setelah membantai orang Banda, Jan Pieterszoon Coen menuju Jakarta dan tiba pada 12 Juli dengan sambutan meriah bagaikan pahlawan besar dengan iring-iringan tembakan meriam dari darat dan laut. Coen bahkan diberi hadiah 3000 guilders dengan sedikit hukuman administratif. Harga penaklukan Banda oleh Coen sangat fantastis; VOC mampu membangun kota Amsterdam, Hoorn, dan sejumlah benteng kokoh di Batavia.

Fakta sejarah ini justru harus dibuka kepada public seluas-luasnya. Semua perlu tahu, bahwa kebijakan colonial dimasa lalu begitu vulgarnya; membayar murah nyawa penduduk jajahannya dengan uang, pesta, dan penghormatan. Sebuah kekejaman yang “Banal”. Kezaliman nyata yang justru dirayakan.

Belakangan, muncul gelombang ikonoklasme di negeri Belanda. Yaitu berbagai protes massa terhadap simbol-simbol kolonialisme di ruang publik. Seperti patung Coen di kota Hoorn yang dulunya dipuja-puja sebagai pahlawan tapi kini berubah menjadi sasaran amuk massa.

Menurut catatan Joella van Dongkersgoed (2019), perdebatan publik tentang J.P. Coen semakin tinggi sejak awal tahun 2018 dipicu oleh pencabutan replika patung Maurits van Nassau dari Mauritshuis di Den Haag dan inisiatif untuk mengganti nama sekolah dasar yang bernama Jan Pieterszoon Coen-school di lingkungan warga “Indonesia” di Amsterdam.

Fenomena ikonoklasme atau yang disebut koran-koran Belanda sebagai “Badai Nieuwe Beelden” ini harus dimengerti sebagai sebuah kesadaran historis baru yang sedang tumbuh dalam kehidupan warga Belanda. Dalam kesadaran baru itu terselip hasrat untuk menuliskan ulang sejarah kehidupan mereka untuk masa depan yang lebih baik. Namun, tentu saja penulis lebih menyarankan kepada public Belanda untuk bersikap lebih bijak terhadap simbol-simbol colonial, dengan cara memperlakukannya secara positif, ketimbang menjadikannya sebagai sasaran vandalism, atau bahkan menghancurkannya.

Truestoriografi dimaksudkan sebagai upaya menuliskan ulang sejarah dengan cara lebih jujur, adil dan terbuka demi masa depan bersama yang lebih baik. Seperti menuliskan seutuhnya siapa sebenarnya Laksamana Pieter Willemszoon Verhoeff, dan menggambarkan siapa sesungguhnya Jan Pieterszoon Coen. Sehingga dimanapun ikon-ikon itu diletakkan, publik tetap dapat memahami dan bersikap lebih rasional. Sehingga, meskipun patung Jan Pieterszoon Coen masih berdiri kokoh di kota Hoorn sampai hari ini, siapapun akan sadar bahwa pada sekujur tubuh Coen berlumur amis darah rakyat Banda.

Van Ittersum, Martine Julia. 2016. Debating Natural Law in the Banda Islands: A Case Study in Anglo–Dutch Imperial Competition in the East Indies, 1609–1621. Routledge Taylor & Francis Group. ISSN: 0191-6599 (Print) 1873-541X (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rhei20

Van Donkersgoed, Joella. 2019. Virtual meeting ground for colonial (re)interpretation of the Banda Islands, Indonesia. Jurnal Wacana Vol. 20 No. 2 (2019): 266-285

Wall, V.I. van de. 1934. “Bijdrage tot de geschiedenis der Perkeniers 1621-1671”,Tijdschrift voor Indische taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 74: 516-580.Multatuli dan Stuiveling 1950:604-617

PALA, NUTMEG TALES OF BANDAOnline exibition By Westfries Museum, Hoorn, Holland www.pala.wfm.nl

Under this chapter you can find the article from Muhammad Farid and an interview with him.

Under this chapter you can find the multi-media installation UN CONDITIONAL from Juul Sadée and her explanation.

PALA, NUTMEG TALES OF BANDA

Pameran online Oleh Museum Westfries, Hoorn, Belanda www.pala.wfm.nl

Di bawah bab ini Anda bisa menemukan artikel dari Muhammad Farid dan wawancara dengannya.

Di bawah bab ini Anda dapat menemukan instalasi multi-media UN CONDITIONAL dari Juul Sadée dan penjelasannya.

ISTANA MINI, Banda Neira

by Juul Sadée

a palace of local and international importance, once, the mansion of the all-powerful Dutch controleur (inspector).

In 1820 this very beautiful governor’s house was built by the French during the short period that they colonized Banda. The Netherlands, or the Batavian Republic was then a vassal state of France.

The architecture was inspired by the facade of the first floor of the opera house in Naples, Italy (1737, destroyed by fire in 1816).

The tiled floors and pillars are made of Italian marble. The marble was not only used as a display of luxury, it was also used for centuries as ballast for the ships that arrived from Europe and brought back merchandise from Banda.

This beautiful house was called small palace, Istana Mini. Ghosts are said to reside there and many, including the author, have personally experienced it.

On September 1, 1834, the last French governor wrote a nostalgic farewell letter, which he scratched into the glass of the window in the room to the left of the main entrance. Then he committed suicide. (Lawrence Blair, Drawn By An Angel, pag. 163, The Banda Islands, Hidden Histories & Miracles of Nature) (https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1163/j.ctt1w76wq4.8?seq=44, pag.62)

This palace is the representative of Banda’s special and ancient history. It was built on some the turning points of history;

– One turning point was the British occupation of Banda shortly before the construction of Istana Mini, namely from 1811 until the fall of Napoleon in 1815. This moment had everything to do with the changing balance of power in Europe after wars between the French and the Brittish. (https://mijngelderland.nl/inhoud/specials/sporen-van-slavernijverleden/de-pattimura-oorlog-strijd-voor-vrijheid-deel-1)

– Istana Mini also marks the changed position that the Netherlands took on Banda. From the beginning of the 16th century, the Dutch trading company, the VOC, traded with Banda, unfortunately by force in order to obtain and maintain the exclusive right to the spice trade. However, in 1798 the VOC had many debts, the Dutch government took over and in 1799 the VOC ceased to exist. (Ontbinding van de Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie, https://isgeschiedenis.nl › nieuws › ontbinding-van-de-ver…)

Banda thus came under the political administration of the Netherlands and became their colony.

ISTANA MINI, Banda Neira

by Juul Sadée

istana penting lokal dan internasional, dulunya, rumah besar kontroler (inspektur) Belanda yang sangat berkuasa.

Pada tahun 1820 rumah gubernur yang sangat indah ini dibangun oleh Prancis selama periode singkat mereka menjajah Banda. Belanda, atau Republik Batavia saat itu adalah negara bawahan Prancis.

Arsitekturnya terinspirasi oleh fasad lantai pertama gedung opera di Naples, Italia (1737, dihancurkan oleh api pada tahun 1816).

Lantai keramik dan pilar terbuat dari marmer Italia. Marmer tidak hanya digunakan sebagai pajangan kemewahan, tetapi juga digunakan selama berabad-abad sebagai pemberat kapal-kapal yang datang dari Eropa dan membawa kembali barang dagangan dari Banda.

Rumah indah ini disebut istana kecil, Istana Mini. Hantu dikatakan tinggal di sana dan banyak, termasuk penulisnya, telah mengalaminya secara pribadi.

Pada 1 September 1834, gubernur Prancis terakhir menulis surat perpisahan nostalgia, yang dia goreskan ke kaca jendela di ruangan di sebelah kiri pintu masuk utama. Kemudian dia bunuh diri. (Lawrence Blair, Drawn By An Angel, hal. 163, The Banda Islands, Hidden Histories & Miracles of Nature) (https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1163/j.ctt1w76wq4.8?seq=44, hal .62)

Istana ini adalah perwakilan dari sejarah khusus dan kuno Banda. Itu dibangun di atas beberapa titik balik sejarah;

– Salah satu titik balik adalah pendudukan Inggris di Banda sesaat sebelum pembangunan Istana Mini, yaitu dari tahun 1811 hingga jatuhnya Napoleon pada tahun 1815. Momen ini berkaitan dengan perubahan keseimbangan kekuasaan di Eropa setelah perang antara Prancis dan Prancis. Inggris. (https://mijngelderland.nl/inhoud/specials/sporen-van-slavernijverleden/de-pattimura-oorlog-strijd-voor-vrijheid-deel-1)

– Istana Mini juga menandai perubahan posisi yang diambil Belanda terhadap Banda. Sejak awal abad ke-16, perusahaan dagang Belanda, VOC, berdagang dengan Banda, sayangnya dengan paksa untuk mendapatkan dan mempertahankan hak eksklusif atas perdagangan rempah-rempah. Namun, pada tahun 1798 VOC memiliki banyak hutang, pemerintah Belanda mengambil alih dan pada tahun 1799 VOC tidak ada lagi. (Mengikat van de Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie, https://isgeschiedenis.nl nieuws ontbinding-van-de-ver…)

Banda dengan demikian berada di bawah administrasi politik Belanda dan menjadi koloni mereka.

Juul Sadée, 14-05-2022